Top

Search

People also search for:

- Home

- SaaS Startup Strategy: A Modern Guide to the Three SaaS Sales Models

Choosing the right go-to-market strategy can make or break a software-as-a-service (SaaS) startup. Joel York’s classic essay on SaaS sales models points out that a misaligned pricing and sales strategy can send a young company into what he calls the SaaS Startup Graveyard. In recent years, the fundamentals haven’t changed: price and — still define the spectrum of sales approaches for SaaS startups.

This blog revisits York’s framework, combines it with updated research and examples, and explores how modern startups can choose and evolve their sales models without losing sight of profitability or growth.

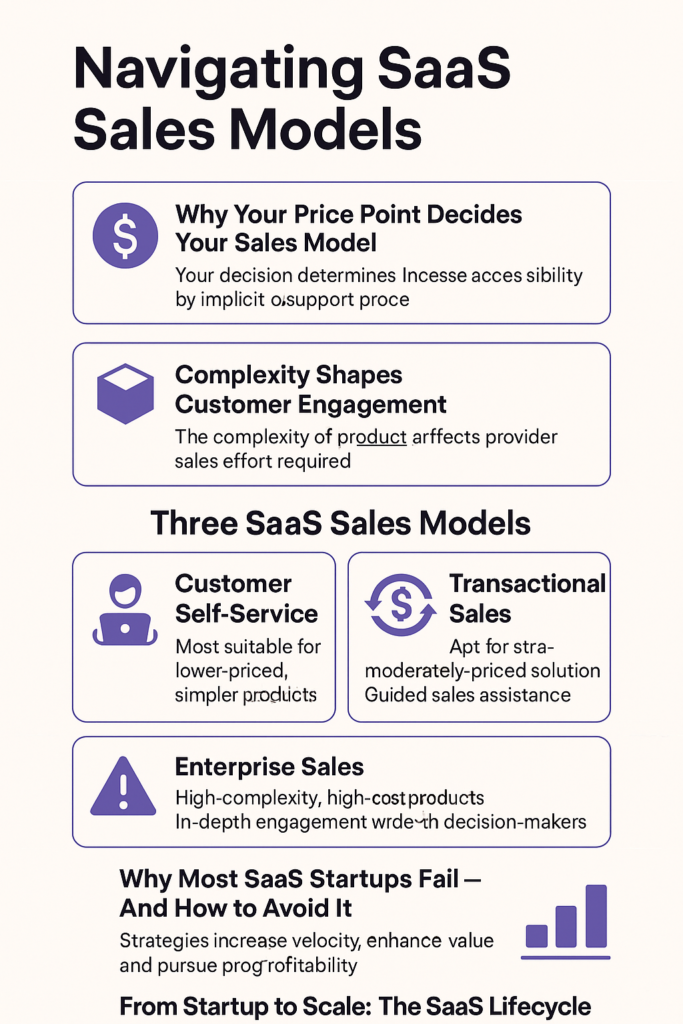

The single most telling statistic for a SaaS business is average selling price (ASP). ASP is the intersection of supply and demand: it reflects the value customers place on your product and the competitiveness of the market, and it constrains your operational metrics such as customer acquisition cost (CAC) and sales volume. For example, if your service sells for $500 per year, you would need to sign up 1,000 accounts annually just to cover the cost of a single dedicated sales representative. At the other extreme, if your ASP is $500,000, one customer could justify a full-time salesperson and high-touch sales motions.

Low ASPs require large target markets and high transaction volumes. To achieve $10 million in revenue with a $1,000 ASP, you need 10,000 paying customers. Higher volume puts pressure on every upstream metric—lead generation, conversion rates, and sales cycles—and increases the need for automation and self-service because human labor is expensive and doesn’t scale well. High ASPs, on the other hand, accompany higher perceived risk: few customers are comfortable purchasing a $50,000 subscription through an online checkout without talking to a human. A startup without brand recognition must provide a personal relationship to overcome buyer anxiety, but a high ASP can pay for the additional sales and support resources.

Price is only one half of the equation; the other is purchase complexity. Complexity refers to how difficult it is for customers to find, understand, try, buy, and use your product. Every barrier that separates your product from the customer slows sales velocity, reduces close rates, and increases costs. You can simplify onboarding and usage, but a certain amount of complexity will always remain, and your chosen sales model must help customers overcome it.

Some products are inherently easy to adopt—for example, single-purpose productivity apps or simple developer tools. Others are complex either because they solve a new type of problem (e.g., collaborative knowledge management) or because they require changes to internal processes (e.g., SaaS ERP). In the latter case, the sales model must provide enough support and education to guide customers through the complexity.

Price and complexity are natural adversaries. High complexity raises costs and therefore requires higher ASPs, but a high price alone does not guarantee that customers are willing to wade through complexity. The art lies in balancing value and effort so that the perceived benefits always exceed the price and the time, fear, and frustration associated with adoption. Failure to achieve this alignment leaves startups stranded in the low-price/high-complexity quadrant.

Price and complexity define a strategic spectrum of sales approaches: customer self-service, transactional sales, and enterprise sales. Mature SaaS vendors may employ all three, but startups typically lack the resources to master more than one model. Each model has distinctive economics, customer expectations, and organizational implications.

When the price point is low and the product is easy to understand and use, the ideal sales model is complete customer self-service. Buyers are both able—they can articulate the value, purchase and use the software—and willing—they perceive minimal risk and effort in the transaction. The self-service model functions with a basic product that is neither costly nor requires a specific audience; customers can purchase online without assistance.

A pure self-service SaaS company has no dedicated salespeople. Instead, marketing owns the revenue number: it creates awareness, produces educational content and automates the entire purchase funnel from discovery to close. Support provides onboarding tools, templates and documentation that enable customers to resolve issues themselves. Because there is no expensive sales force, the model relies on huge volumes and low CAC. This approach is common in commodity productivity tools (e.g., Zoho or 37 signals) or in many consumer-oriented SaaS offerings.

Self-service scales beautifully: once the marketing and product engines are built, marginal costs drop and customer acquisition becomes largely automated. However, it works only when the product is simple, the user can find and understand it easily and the price is low enough to discourage hesitation. Forcing a complex or expensive product into a self-serve channel often results in high churn and unhappy customers. Self-service products typically target small to medium businesses, have low complexity, offer minimal assistance, enjoy short sales cycles and command low to moderate prices.

As the average selling price increases and customers expect more assurance, purely self-service systems no longer suffice. Customers want to know that real people are behind the URL. High ASP brings higher expectations such as signed contracts, premium SLAs, invoicing, and the ability to talk to someone when problems arise. This drives the sales model toward transactional sales: efficient, high-volume operations with short sales cycles and rapid onboarding.

In the transactional model, inside sales representatives handle inquiries and close deals, supported by online content and marketing automation. Reps are trained, incentivized and measured on transaction volume. Marketing continues to generate and qualify leads, removing roadblocks and educating prospects. Support teams provide timely assistance across a range of service levels, from limited pre-sale help to premium post-sale support; they rely on tools, training, and metrics that enable high efficiency and are complemented by customer self-service resources.

The transactional model is appropriate for mid-market companies using moderately complex products. It requires a sales team engagement, provides moderate assistance, aims for medium-length sales cycles, and usually commands moderate price points. Examples include SaaS products that automate well-defined business processes with a bit of internet twist, such as marketing automation or customer support platforms.

Transactional sales models seek a balance between automation and human interaction. The organisation must handle significant volumes while still providing enough guidance to close deals. Pricing must be high enough to cover the cost of sales, yet low enough to entice mid-market customers. Achieving this balance requires careful segmentation (identifying high-value accounts), clear processes (e.g., fast demos, free trials), and alignment between marketing, sales, and support.

Some startups enter markets where each customer brings such high value and faces such high complexity that the natural starting point is enterprise sales. Enterprise sales involve large contracts, long sales cycles, and a highly personalized buying process. This model is typical for cutting-edge Internet marketing tools used by big brands or feature-rich suites that automate core business processes for mid-to-large enterprises. Enterprise sales target very large companies, involve high-complexity products, require dedicated team support, offer high-touch personalized assistance, and operate with long sales cycles and high price points.

Enterprise SaaS providers deploy territory sales representatives who focus on a narrow set of target accounts. These reps are supported by product marketing and sales engineering resources at the deal level. Marketing shifts from mass campaigns to high-end initiatives that build brand awareness, cultivate relationships, and supply detailed sales tools such as ROI calculators. Support becomes high-touch, often including on-site issue resolution, and is tailored to the specific needs of individual clients. The emphasis is on trust, risk reduction, and customisation.

The enterprise model requires significant investment in personnel and time. Deals may take months or even years to close, and a single lost contract can have a material impact on revenue. Startups pursuing enterprise sales must ensure their ASP and gross margins are sufficient to sustain long sales cycles, pilots and heavy support obligations. They should also safeguard against chasing extremely large customers too early; doing so can distract the company and ruin economies of scale. On the other hand, successful enterprise SaaS providers enjoy long-term contracts, high customer retention and the potential to expand within accounts.

High complexity and low prices are a toxic combination. Startups that offer complex products at low prices end up hand-holding every free customer as if each were an enterprise sale, which is not sustainable. The concept of a “Startup Graveyard” refers to companies that fail because their sales model cannot support their price–complexity mix. There are three strategies for avoiding this fate:

The holy grail lies at the opposite end of the graveyard: high ASP combined with low complexity. Google Ads and Amazon Web Services exemplify this quadrant—customers routinely spend six-figure sums online with minimal human interaction. While few startups can achieve this immediately, striving toward simplicity and automation even at higher price points yields compounding benefits.

A SaaS startup rarely remains in one sales model forever. As it matures, growth aspirations lead to expansions into adjacent customer segments and products. The most common evolutionary path starts with a self-service product, then adds features, modules and pricing tiers to move up market. A nimble startup can progress from $10 monthly recurring revenue (MRR) to $100, then $1,000 and $10,000 as it layers on value.

However, scaling up is not trivial. Behind the simple tactics lie tectonic strategic, operational, and cultural shifts. The self-service model is rooted in a mass-market, low-cost competitive strategy. The enterprise model assumes a highly differentiated product characterised by cutting-edge innovation. Maintaining the simplicity of the original self-service offering while introducing more complex products and purchase processes requires careful planning. Questions arise: Should new features be separate products or modules? Should transactional sales skim the “cream” of self-service prospects or rely on separate lead-generation vehicles? Are enterprise customers just grown-up transactional customers or an entirely different species? Moving upmarket is often easier than moving down, but it is not easy without inadvertently neglecting the lower-priced segment.

When contemplating expansion, consider the following:

The choice of a sales model is not a one-time decision. It is a strategic commitment that aligns your pricing, product complexity, organisational structure, and go-to-market activities. Customer self-service works when the product is simple, the market is huge, and the price is low. Transactional sales become necessary as prices rise and customers demand human reassurance. Enterprise sales fit when products are complex, contracts are large, and buyers require hands-on guidance. Straying into a mismatch—complex products sold cheaply or simple products sold via heavy sales efforts—leads to inefficiency and potential failure.

Modern SaaS companies must also remember that customer success drives revenue. Long sales cycles, churn, and competition are persistent challenges. Measuring and improving performance through CAC, MRR, churn, LTV, and ARR ensures that your sales model is financially sustainable. Focusing on customer outcomes promotes loyalty, renewals, and referrals. Finally, the organisational agility to evolve from one model to another—without abandoning your existing customers—separates the survivors from the inhabitants of the Startup Graveyard.

We manage and optimize your IT infrastructure end-to-end.Ensuring stability, security, and operational continuity.

Consult IT Experts

Hi! I’m Aminah Rafaqat, a technical writer, content designer, and editor with an academic background in English Language and Literature. Thanks for taking a moment to get to know me. My work focuses on making complex information clear and accessible for B2B audiences. I’ve written extensively across several industries, including AI, SaaS, e-commerce, digital marketing, fintech, and health & fitness , with AI as the area I explore most deeply. With a foundation in linguistic precision and analytical reading, I bring a blend of technical understanding and strong language skills to every project. Over the years, I’ve collaborated with organizations across different regions, including teams here in the UAE, to create documentation that’s structured, accurate, and genuinely useful. I specialize in technical writing, content design, editing, and producing clear communication across digital and print platforms. At the core of my approach is a simple belief: when information is easy to understand, everything else becomes easier.